BTW, his name is Brandon!

@BrandSanderson I apologize for writing four reviews of your books and still calling you Brian for some reason. :)

— Siderite Zackwehdex (@Siderite) September 11, 2016

@BrandSanderson I apologize for writing four reviews of your books and still calling you Brian for some reason. :)

— Siderite Zackwehdex (@Siderite) September 11, 2016

I was in some sort of American campus, one of those where they found a gimmick to show how cool they are. In this case it was reptiles. Alligators were moving on the side of the street, right next to people. They would hiss or even try to bite if you got close enough. I was moving towards the exit, which was close to the sea and leading into a sort of beach, and I was wondering what would happen if one of these large three meter animals would bite someone. And suddenly something happened. Something large, much larger than a crocodile, came out of the water and snapped a fully grown adult alligator like a stork snatches frogs. What was that thing? A family of three was watching, fascinated, moving closer to see what was going on. "Are these people stupid?" I thought.

I was in some sort of American campus, one of those where they found a gimmick to show how cool they are. In this case it was reptiles. Alligators were moving on the side of the street, right next to people. They would hiss or even try to bite if you got close enough. I was moving towards the exit, which was close to the sea and leading into a sort of beach, and I was wondering what would happen if one of these large three meter animals would bite someone. And suddenly something happened. Something large, much larger than a crocodile, came out of the water and snapped a fully grown adult alligator like a stork snatches frogs. What was that thing? A family of three was watching, fascinated, moving closer to see what was going on. "Are these people stupid?" I thought.  Copyright is something that sounds, err... right. It's about keeping the profits of the sale of work to its author. If I write a book, I expect to get the money from it, not somebody who would print it and sell it in my name. With the digital revolution, copy costs collapsed to zero: anyone can copy anything and spread it globally for free. So what does that mean for me, the author? Well, it sucks. The logical thing for me is to try to fight for my rights, turn to the law which is supposed to protect me, find technical ways of making copying my work harder, preferably impossible, going for the people who are chipping away at my hard earned profits.

Copyright is something that sounds, err... right. It's about keeping the profits of the sale of work to its author. If I write a book, I expect to get the money from it, not somebody who would print it and sell it in my name. With the digital revolution, copy costs collapsed to zero: anyone can copy anything and spread it globally for free. So what does that mean for me, the author? Well, it sucks. The logical thing for me is to try to fight for my rights, turn to the law which is supposed to protect me, find technical ways of making copying my work harder, preferably impossible, going for the people who are chipping away at my hard earned profits. No, it's not about mine, although this blog has had its ups and down. What I want to talk about is the list of blogs I am following and how it (d)evolved.

No, it's not about mine, although this blog has had its ups and down. What I want to talk about is the list of blogs I am following and how it (d)evolved. The Emperor's Soul is set in the same world as Elantris, but for all intents and purposes it is a standalone story. It's not a full size book, but it's a bit longer than a short story. In it we find a type of magic called Forging, by which someone can carve and use a complicated seal to change the history of an object or, indeed, a soul. The forging needs to be very precise and as close as possible to the actual history of the target, otherwise the magic doesn't "stick". So what must a brilliant forger do in order to do the forbidden soul forging? They must know their target so intimately that they can't ultimately hurt them.

The Emperor's Soul is set in the same world as Elantris, but for all intents and purposes it is a standalone story. It's not a full size book, but it's a bit longer than a short story. In it we find a type of magic called Forging, by which someone can carve and use a complicated seal to change the history of an object or, indeed, a soul. The forging needs to be very precise and as close as possible to the actual history of the target, otherwise the magic doesn't "stick". So what must a brilliant forger do in order to do the forbidden soul forging? They must know their target so intimately that they can't ultimately hurt them. I've read the book in a day. Just like the other two in the series (Steelheart and Firefight), I was caught up in the rhythm of the characters and the overwhelming positivity of the protagonist. Perhaps strange, I kind of missed descriptions in this one, as both locations and characters were left to the imagination and everything was action and dialogue.

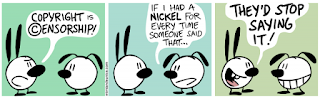

I've read the book in a day. Just like the other two in the series (Steelheart and Firefight), I was caught up in the rhythm of the characters and the overwhelming positivity of the protagonist. Perhaps strange, I kind of missed descriptions in this one, as both locations and characters were left to the imagination and everything was action and dialogue. The Mirror Thief is a really interesting book. It is well written, original in ideas and Martin Seay has his own unique writing style. It is also a very deceptive book, always changing shape, misleading the reader over what he is actually reading.

The Mirror Thief is a really interesting book. It is well written, original in ideas and Martin Seay has his own unique writing style. It is also a very deceptive book, always changing shape, misleading the reader over what he is actually reading. I have been playing a little with the Houdini chess engine and Chess Arena. I limit the ELO of the engine to a set value and then I try to beat it. It's not like playing a human being, but saves me the humiliation of being totally thrashed by another person :) Plus I didn't have Internet. In this case the ELO was set to 1400.

I have been playing a little with the Houdini chess engine and Chess Arena. I limit the ELO of the engine to a set value and then I try to beat it. It's not like playing a human being, but saves me the humiliation of being totally thrashed by another person :) Plus I didn't have Internet. In this case the ELO was set to 1400. My mind has been wandering around the concept of gamification for a few weeks now. In short, it's the idea of turning a task into a game to increase motivation towards completing it. And while there is no doubt that it works - just check all the stupid games that people play obsessively in order to gain some useless points - it was a day in the park that made it clear how wrong the term is in connecting point systems to games.

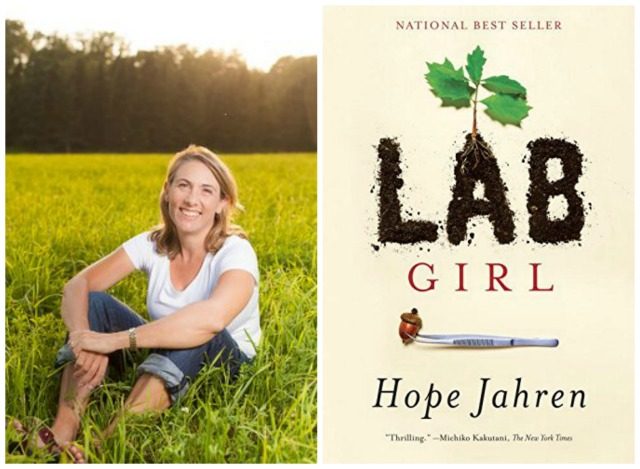

My mind has been wandering around the concept of gamification for a few weeks now. In short, it's the idea of turning a task into a game to increase motivation towards completing it. And while there is no doubt that it works - just check all the stupid games that people play obsessively in order to gain some useless points - it was a day in the park that made it clear how wrong the term is in connecting point systems to games. Lab Girl should have been the kind of book I like: a deeply personal autobiography. Hope Jahren writes well, also, and in 14 chapters goes through about 20 years of her life, from the moment she decided she would be a scientist to the moment when she was actually accepted as a full professor by academia. She talks about her Norwegian family education, about the tough mother that never gave her the kind of love she yearned for, she talks about misogyny in science, about deep feelings for her friends, she talks about her bipolar disorder and her pregnancy. Between chapters she interposes a short story about plants, mostly trees, as metaphors for personal growth. And she is an introvert who works and is best friends with a guy who is even more an introvert than she is. What is not to like?

Lab Girl should have been the kind of book I like: a deeply personal autobiography. Hope Jahren writes well, also, and in 14 chapters goes through about 20 years of her life, from the moment she decided she would be a scientist to the moment when she was actually accepted as a full professor by academia. She talks about her Norwegian family education, about the tough mother that never gave her the kind of love she yearned for, she talks about misogyny in science, about deep feelings for her friends, she talks about her bipolar disorder and her pregnancy. Between chapters she interposes a short story about plants, mostly trees, as metaphors for personal growth. And she is an introvert who works and is best friends with a guy who is even more an introvert than she is. What is not to like? About 25 years ago I was getting Compton's Multimedia Encyclopedia CD-ROM as a gift from my father. Back then I had no Internet so I delved into what now seems impossibly boring, looking up facts, weird pictures, reading about this and that.

About 25 years ago I was getting Compton's Multimedia Encyclopedia CD-ROM as a gift from my father. Back then I had no Internet so I delved into what now seems impossibly boring, looking up facts, weird pictures, reading about this and that.  I am writing this post to rant against subscription popups. I've been on the Internet long enough to remember when this was a thing: a window would open up and ask you to enter your email address. We went from that time, through all the technical, stylistic and cultural changes to the Internet, to this Web 3.0 thing, and the email subscription popups have emerged again. They are not ads, they are simply asking you to allow them into your already cluttered inbox because - even before you've had a chance to read anything - what they have to say is so fucking important. Sometimes they ask you to like them on Facebook or whatever crap like that.

I am writing this post to rant against subscription popups. I've been on the Internet long enough to remember when this was a thing: a window would open up and ask you to enter your email address. We went from that time, through all the technical, stylistic and cultural changes to the Internet, to this Web 3.0 thing, and the email subscription popups have emerged again. They are not ads, they are simply asking you to allow them into your already cluttered inbox because - even before you've had a chance to read anything - what they have to say is so fucking important. Sometimes they ask you to like them on Facebook or whatever crap like that.

The Brain that Changes Itself is a remarkable book for several reasons. M.D. Norman Doidge presents several cases of extraordinary events that constitute proof for the book's thesis: that the brain is plastic, easy to remold, to adapt to the data you feed it. What is astonishing is that, while these cases are not new and are by far not the only ones out there, the medical community is clinging to the old belief that the brain is made of clearly localized parts that have specific roles. Doidge is trying to change that.

The ramifications of brain plasticity are wide spread: the way we learn or unlearn things, how we fall in love, how we adapt to new things and we keep our minds active and young, the way we would educate our children, the minimal requirement for a computer brain interface and so much more. The book is structured in 11 chapters and some addendums that seem to be extra material that the author didn't know how to properly format. A huge part is acknowledgements and references, so the book is not that large.

These are the chapters, in order:

There is much more in the book. I am afraid I am not making it justice with the meager descriptions there. It is not a self-help book and it is not popularising science, it is discussing actual cases, the experiments done to back what was done and emits theories about the amazing plasticity of the brain. Some things I took from it are that we can train our brain to do almost anything, but the training has to follow some rules. Also that we do not use gets discarded in time, while what is used gets reinforced albeit with diminishing efficiency. That is a great argument to do new things and train at things that we are bad at, rather than cement a single scenario brain. The book made me hungry for new senses, which in light of what I have read, are trivial to hook up to one's consciousness.

If you are not into reading, there is an one hour video on YouTube that covers about the same subjects:

[youtube:sK51nv8mo-o]

Enjoy!

After a month of trial with no one to complain of HTTPS issues, I've decided to set the blog to redirect normal connections to the secure URL. Let me know if you experience any problems.

After a month of trial with no one to complain of HTTPS issues, I've decided to set the blog to redirect normal connections to the secure URL. Let me know if you experience any problems.

Democracy, like any other system of government or political system, is designed to keep the powerful in the driver's seat. It's not about the good of the people, unless they hold power. It was invented and implemented at times when having a large group of people supporting you meant something, gave you the ability to do things. Any other system: theocracy, tyranny, feudalism, communism, fascism... they all do the same thing and fail when the group they support fails to maintain power. Democracy is not about the little people, it's about how fast a system can adapt to changes in the structures of power. It is just the "agile" version of the same old thing. By declaring its ruling group "the people", democracy can survive any political change. The system outlives groups and groups of "people".

Democracy, like any other system of government or political system, is designed to keep the powerful in the driver's seat. It's not about the good of the people, unless they hold power. It was invented and implemented at times when having a large group of people supporting you meant something, gave you the ability to do things. Any other system: theocracy, tyranny, feudalism, communism, fascism... they all do the same thing and fail when the group they support fails to maintain power. Democracy is not about the little people, it's about how fast a system can adapt to changes in the structures of power. It is just the "agile" version of the same old thing. By declaring its ruling group "the people", democracy can survive any political change. The system outlives groups and groups of "people".