No one knows how to interview people

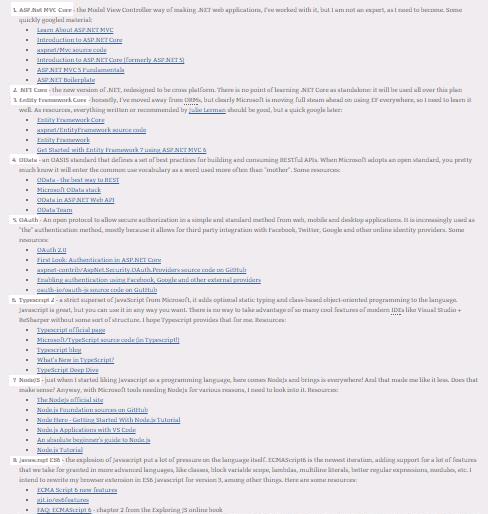

After a slightly misused sabbatical year, I went through a period of trying to get hired. That means interview after interview with people that were assessing my fit within their company. Man, that sucked! I mean, I am a white male professional in a business where everyone is looking for personnel and still it was frustrating, demeaning and painful. But I am not here to complain (maybe a little :) ), only to share my experience and my... constructive criticism.

After a slightly misused sabbatical year, I went through a period of trying to get hired. That means interview after interview with people that were assessing my fit within their company. Man, that sucked! I mean, I am a white male professional in a business where everyone is looking for personnel and still it was frustrating, demeaning and painful. But I am not here to complain (maybe a little :) ), only to share my experience and my... constructive criticism.The story

OK, so first off, the only other real experience in looking for work was more than ten years ago and then I was an absolute beginner on the market. However, back then I knew I was a nobody, while now I know that my experience and passion put me way up there as usefulness and value go. I may have started off this campaign with an unhealthy level of smugness, but it goes off quickly, I assure you.

I am lucky that I had this year of experimenting before I started looking, which allowed me to treat it as any other experiment: I accepted almost all interviews and I went diligently through the entire process, no matter my personal opinion about the company. That helped a lot as a learning experience; while I know how to code, it quickly became apparent that I have no idea how to convince others about it. I set up to try everything, learn from it, while continuing to be principled. In my mind that meant completely honest. I didn't expect company people to be honest with me, but that was on them. I would be a perfect WYSIWYG candidate. Better to fail fast, rather than have a miserable experience in the relationship. BTW, that is also my strategy with girls, which explains why I am virgin. I stuck to my guns, though.

The experience

I am not going to name names here. This is not about how awful some companies may have been. It is all about my perception of the hiring process. And it is that it sucks!

I don't know if in other fields it goes smoother, but imagine this: the only people that have any idea about how to hire people are the HR people and they have no idea what software programming is like. I could be married with an HR manager and she still would not know anything about software development. The technical people may know how to code, but they have no idea how to determine if the other person is any good and if you are a technical person you are definitely not an human resources person. I applaud people who can be both, mostly because I have not met one and I can't think of any scenario that would produce such an individual other than some radioactive alien arthropod biting a regular person.

Funny enough, compared with my past, is that HR mostly liked me while the technical people (the majority more than a decade younger) mostly dismissed me. At first I felt like a complete impostor (of course), my self esteem plummeted (which didn't help any), and I was about to beg for a job (which is what most people do, I hear). However, I tried to see the situation from the point of view of the people trying to hire me (I know: shocking!) and I could understand their situation and empathize. Think about it. How would you test someone for a programming job? Who would you call in that meeting? What would be the salary that you would budget for that person (in EUR, after taxes)?

Did you really think about it? Come on, make an effort. I guarantee it's worth it.

OK, so the HR people looked at my resumé and saw that I have had a lot of stable jobs before in all kinds of environments. I was a pleasant enough person (I mean, for a techie, which means without obvious homicidal tendencies) with a very good understanding of the English language. No obvious conflicts, although I may have been too honest in my (err.. constructive!) criticism of past employment. I mean, come on!, every dev can tell you that managers don't know what they're doing, right? If I think about it, the job of the HR department seems fairly simple to me: look for a candidate that fits the profile, lure them in, do the most simplistic psychological screening possible, then pass it along to the tech department. It's something that AIs will probably take over soon. I may fondly look backwards to these times, when there existed people that were actually biased towards me! The typical HR person is a girl. Now, if I am being insensitive here, I apologize, but if you want to seduce a tech to the point where he would do anything to come to you, you use a nice, sexy girl. It's only natural when devs are mostly male virgins. To be honest, these girls could have hated me or wanted me to have sex with them and I would have had no clue whatsoever. If they said it, I took it for granted. If they lied, again, it's on them. If they remained quiet, then I couldn't parse it into text and who's fault is that?

So then there was the tech interview. You have some guy who thinks he's God because he can code and maybe have some overview that is slightly larger than those of his juniors. He is young, probably coming from some technical university (yes, in Romania people actually do look for coding work after studying Computer Science). He has no idea how he needs to conduct an interview, but admitting to that, even to himself, is a bit too discordant with his view of his person. So he does what every tech would do in this situation: he Googles it. You might be amazed, but Google actually turns up some good advice, but you must be willing to admit that your expectations for how to do that may have been completely wrong. So he does the second thing anyone does when Googling: looks for links that validate their own beliefs (and also have some template for interviews that they can quickly print and use).

Am I being unfair here? Probably. But it is a good theory to explain the types of interviews that I had and how they all seemed carbon copied after each other. The template is basically this:

- an algorithmic question, such as: how do you refresh a sorted list from another complete sorted list, or how do you intersect two sorted lists, or how do you search into a sorted list or... wait a minute, are they all about bloody sorted lists?

- general algorithmic knowledge questions, such as: what is the difference between a list and a linked list, or an array and a list, what are the complexities of operations on lists. Pretty much there has to be a data container there.

- general language knowledge questions, such as: behavior of some implementation in a specific language, the results of SQL queries, characteristics of SQL indexes, some HTML stuff, the life cycle of ASP.Net if you are really lucky...

- tools and ways of working in tech from previous employers. Here they are actually interested, because while they appear to be judging everything you say, they actually want to hear of better ways of working themselves.

- questions about a project you really liked or had a lot of influence over. Yeah! And while you feel like an idiot because no one ever let you work on a project that you think was special, the interviewer learns from your experience and adapts it to their crappy project.

- asking you if you have questions for them and looking like they expect you to have some really sensible and relevant questions when all you want is to know if they want to have you or not

The existence of the first step is being fed by sites like HackerRank, Codility and CodingGame, which should never be considered as anything else than learning tools, if not just silly games. However, since these people went through grueling university lectures about algorithms and then inflated their own ego playing on the web sites above they assume you should know about them too. It doesn't matter that they rarely found use of any of it when working on their projects, they just push it under the vague concept of "wanting to see how you think". However, they are not logical problems (like they used to put 5 years ago, copying from Google and the like), they are very specific coding situations. You may know the exact solution - because you played around with algorithms when bored - or you might have no idea how to solve the problem.

And here you are now, facing a guy that looks critically at you, while trying to think of the problem, finding the best solution and doing it before the guy gets bored. It will take him about 60 seconds to get bored, too, as he already knows the answer to the question and he feels it's obvious and the only one possible. Hell, he knew how to solve this before he even left university! It doesn't matter that several scenarios fight for supremacy in your head, that for each there is another solution, that the very simple solution feels too simple and your brain is wracking itself to find another one - that would be probably either wrong, over engineered or both. And you want, you really want to implement a three step algorithm that you know always works (1. Google it 2. Think of something better 3. Use the best implementation found), but you believe it would be perceived as not knowing your stuff. I mean, what if you are at work and your Internet dies? Surely you need to solve the problem anyway, right?

In truth, the lucky scenario is if they send you to HackerRank or something similar to solve a technical test before you meet with anybody. That goes over fast and easy, while you hack comfortably in your underwear and you have no stress about who is thinking what. The unlucky scenario is that you get a guy who thinks you are not a true developer unless you are working on open source projects on GitHub in your spare time. Oh, and they need to be interesting to him.

Yet, after you go through the first two steps, the rest are a breeze: you know your stuff, you know your languages, you can even think of a project or two that had something remotely instructive in them. It feels like you went over a bump, but now you can go full speed. They ask you various things about your past experience, you gladly oblige, make a few jokes, get some laughter, start to feel good about yourself. Surely, you will pass the interview.

And then you get "the call", where you know you have failed from the tone of the HR girl who needs to tell you that they won't be going further with it. You still hope against hope while she goes on and on and on through her complex script of letting you go easy. She thinks she's being thoughtful, yet you are a tech and you want the answer first and the explanations after. And you despair. Obviously, you suck. You will never get a job. You are worthless, less than worthless, a complete buffoon. And here you were, thinking that years of successful work with people that appreciated your efforts meant anything. When was the last time you learned something new anyway? Last month? Three programming languages and five new frameworks launched since then, not to count the new versions of old frameworks that you never got around to master. Who were you kidding? There are ten year olds that can code better than you. And they are not married yet! You know getting a dog will ruin your career. You are a fossil, admit it! In five years you will be begging for food on the street with a sign that says "Will code for bread". And you know what? You are right: you are an idiot!

I cannot claim absolute truth here, because I don't have enough data to arrive at a clear conclusion. That is because when they flunk you, the sweet HR girl stops contacting you altogether. If you are lucky the company didn't use their own human resources and instead you arrived through a dedicated HR firm (headhunters) and they have the decency to not only tell you didn't pass, but also make the effort to tell you why. The people you maybe knew at that company and were really supportive of you joining their team drop from the face of the Earth. Clearly, you were too stupid to work there, so they cut you off. At the very best you are an emotional mess and they don't want to have anything to do with that. So the next section is mostly speculation, but I will try to make it sound good.

The Explanation

There are a zillion reasons people don't want you in their team on the specific project they are working on and that have nothing to do with your value as a human being.

You might have asked for a sum that is too large for what they were prepared to offer. Even if you are that valuable, they are too cheap for it. It's like the girl who dumps you without telling you why (maybe mumbling something about you being insensitive) because you said you liked anal and she was afraid to try it. It may also be because you think you deserve more than people are actually willing to pay in general. That's on you. However, the correlation between your skills and your pay is not linear. It mostly depends on the market. After all, you are trying to sell yourself. You are already a whore, now you are just negotiating on the price. Today you may be a hero, tomorrow you will be the guy that made some money in that [enter fleeting fad] boom and lost it all in the subsequent crash.

People might put a lot of value on algorithms. It may be a good decision, because in their project they often meet situations where good algorithmic knowledge saves the day. If you are not good at it, or you couldn't prove it in the makeshift interview you flunked, they have every right to not go through with it. They might also not know any other way to test your knowledge and be too lazy to actually look for value in people. There a lot of other similar reasons that you may file under this scenario. They wanted something specific from you, didn't tell you and you don't have it.

They think you are old. And you may just well be. Age discrimination aside, why should they hire someone like you when they perceive the same value from a guy 20 years younger - and way cheaper? If I had to chose, I would have no qualms whatsoever. This is also linked to expectations. Remember when you were counseled to try to move to a manager position before you got to [enter ridiculously low number here]? That translates to the expectation that after that age, being a simple techie means there is something wrong with you. This will never ever change. Look at the age average in all the big companies: it's about 30. Startups even less, around 22. That doesn't mean you need to become a manager, I am sure old managers feel just as threatened. Plus, you might really suck as a manager. I know I would. Unofficial sources say that even the places that usually hire people for experience (like government jobs) stop looking at resumes for people over 45. Age does matter, so plan for it.

And then there is the idea that if you are inexperienced you can learn quicker the things that "you really need", like that framework that became famous while you were reading this blog post. You may be experienced, but will they need to fight with you on whether to use ASP.Net MVC over ASP.Net forms? (or is ASP.Net MVC obsolete already? I don't know, I was blogging). I don't know if that's true. I did learn quicker when I was young, but that was mostly by failing miserably again and again. On the other hand a job position where you are hired for your ability to fail your tasks sounds pretty good, doesn't it?

There is also the personal thing. You might have rubbed someone the wrong way. That means not that you are an awful person, but that you just don't match with a person who you might have had to work with if they went forward and hired you. Again, want to be married with the girl that hates you, no matter how big her boobs are? You may be an asshole, but maybe the other person was, too. Some people might feel threatened by you, either because you threatened their life if they don't hire you or because they think you are way sexier than them and you would cock block their attempts to woo the HR girl. You won't become a better person by trying to be liked by everyone. They might have hated your shirt, for example, the one that you thought would look really professional, but they saw as threatening, because they usually work in shorts and t-shirts. Point is, they had some expectations and you didn't meet them. Were they justified? You don't know and you shouldn't care.

The position you would be working on is equally important. You might be a brilliant web developer, but if they actually wanted a server guy, or viceversa, they will drop you. They will not admit that they were not specific in their job description, of course, and instead just blame you for not being "a good fit". Imagine you are a cube that is crying it didn't fit in a circular hole. Ridiculous, right? I mean, would the tears be blocky? As a specific example: I went somewhere for several interviews. I was "a perfect match" for one and not the right person for another. The JD document they sent for both positions was identical.

Solutions

Since I code and have an overview on life, I can definitely tell you how interviews should be conducted, but you will have to buy the paid version of this blog for that. See, I am learning fast, in one phrase I was both a tech, a business person and an asshole.

The truth is that the only way I could think of that wasn't insulting to everyone's intelligence was to actually show them a computer, a real problem, and let them fix it with me watching and helping next to them. And it still wouldn't be sufficient. If it were "real" enough, then it would take time to understand all of the aspects of the problem. The guy might be overly nervous with me next to him. I know people that can only work when no one is watching, and they do great work. Plus, they may have experience on that exact problem and suck at anything else.

Unfortunately, in all my interviews the only tools that I had to work with were pen and paper. Putting aside the fact that I don't even understand my own writing, the last time I had to actually write anything on paper was... oh yeah, the last time I was looking for a job. Does it make sense to conduct software development interviews with no computer? I would say no.

Conclusions

There is a schism between what they expect and what you expect, what you think of yourself and what they do. That is the real reason behind every failed interview. It doesn't really matter if they had unrealistic expectations, but it matters a lot if you had. Like every experiment: acquire data, reason about the data, propose a theory that explains it, test it against new data. The best way to achieve anything is to change your behavior towards the goal. The important thing here is to define the goal. Is it to get hired at any and all costs? Or is it to find the place where you will enjoy working, keep growing and be appreciated for your efforts?

In the end it so happens that not only did I get hired at the company I was aiming for, but I did it on the position I feel I was best suited for, rather than some mediocre second best. Like with dating girls, it is worth waiting for the right one. And with software, you get to do side projects, too!