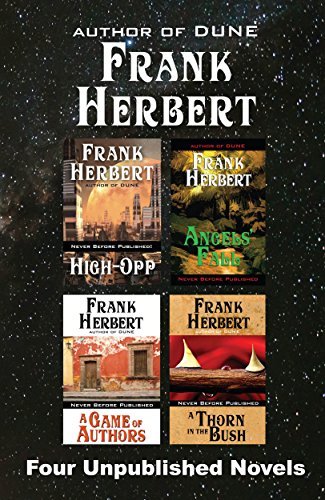

Four Unpublished Novels: High-Opp, Angel’s Fall, A Game of Authors, A Thorn in the Bush, by Frank Herbert

We all know Frank Herbert for his science fiction work, mainly Dune, but before he became famous by publishing that, he wrote may short stories and novels. This collection published in 2013 holds four of the pre-Dune novels he never got to publish. I found the stories very Herbert, kind of dated and, except the first one's premise, non-sci-fi. Yet they show how the ideas that went through Herbert's brain evolved in time.

The novels in the collection are: High-Opp, Angel's Fall, A Game of Authors and A Thorn in the Bush.

High-Opp

It shows the irreverent cynicism that the author had towards governments and social systems, but with a yet unpolished writing style. The story shows how a brilliant man, stuck in the middle of the social hierarchy of a communist-like government is betrayed and then manipulated by various groups. As the strong '50s male archetype he manages to outsmart and outfight everybody.

Angel's Fall

This is an interesting story about a damaged air vehicle floating on a river while enemies are trying to catch and destroy it. It's not sci-fi, as the air vehicle in question is a floatplane and the enemies are Amazon native tribes. But if you thought I was talking about the jungle part of The Green Brain, I would understand, as it's basically the same story without the sci-fi elements!

A Game of Authors

A weird story about an American journalist travelling to Mexico for a story, while being manipulated and attacked by various interested parties. It felt really dated and not well thought through. The characters were a joke, particularly the female ones. It was supposed to be a "brave resourceful man" story, but it felt like a "clueless American still doesn't believe people would try to kill him" thing.

A Thorn in the Bush

This felt like the least Herbert story of them all, even if it did focus on the internal drive and motivation of people. It's the story of an old madame who, having moved to Mexico and become respectable, tries to boss everybody based on her own past traumas and present delusions. Strange to have a female main character in a Herbert novel. It was not bad, but it was the farthest from sci-fi you will ever read.

With this I have ended reading everything Herbert wrote and I could find. From them all, Dune is of course on top of it all, but also Destination: Void (not the series, but the original book), Hellstrom's Hive, The White Plague and perhaps surprisingly Soul Catcher. There are lot of other good stories, but I loved these ones. Phew! It's over! :) It was nice, but a little tiring.