Intro

An

adapter is a

software pattern that exposes functionality through an interface different from the original one. Let's say you have an oven, with the function

Bake(int temperature, TimeSpan time) and you expose a

MakePizza() interface. It still bakes at a specific temperature for an amount of time, but you use it differently. Sometimes we have similar libraries with a common goal, but different scope, that one is tempted to hide under a common adapter. You might want to just cook things, not bake or fry.

So here is a post about good practices of designing a library project (complete with the use of

software patterns, ugh!).

TL;DR; take me to Principles for adaptersExamples

An example in .NET would be the

WebRequest.Create method. It receives an

URI as a parameter and, based on its type, returns a different implementation that will handle the resource in the way declared by the WebRequest. For HTTP, it will used an

HttpWebRequest, for FTP an

FtpWebRequest, for file access a

FileWebRequest and so on. They are all implementations of the abstract class

WebRequest which would be our adapter. The Create method itself is an example of the

factory method pattern.

But there are issues with this. Let's assume that we have different libraries/projects that handle a specific resource scope. They may be so different as to be managed by different organizations. A team works on files, another on HTTP and the FTP one is an open source third party library. Your team works on the WebRequest class and has to consider the implications of having a Create factory method. Is there a switch there? "

if URI starts with http or https, return new HttpWebRequest"? In that case, your WebRequest library will need to depend on the library that contains HttpWebRequest! And it's just not possible, since it would be a circular reference. Had your project control over all implementations, it would still be a bad idea to let a base class know about a derived class. If you move the factory into a factory class it still means your adapter library has to depend on every implementation of the common interface. As

Joe Armstrong would say

You wanted a banana but what you got was a gorilla holding the banana and the entire jungle

.

So how did Microsoft solve it? Well, they did move the implementation of the factory in another creator class that would implement

IWebRequestCreate. Then they used configuration to associate a prefix with an implementation of WebRequest. Guess you didn't know that, did you? You can register your own implementations

via code or configuration! It's such an obscure feature that if you Google

WebRequestModulesSection you mostly get links to source code.

Another very successful example of an adapter library is

jQuery. Yes, the one they now say

you don't need anymore, it took industry only 12 years to catch up after all. Anyway, at the time there were very different implementations of what people thought a web browser should be. The way the

DOM was represented, the Javascript objects and methods, the way they actually worked compared to the way they should have worked, everything was different. So developers were often either favoring a browser over others or were forced to write code for each possible version. Something like "

if Internet Explorer, do A, if Netscape, do B". The problem with this is that if you tried to use a browser that was neither Internet Explorer or Netscape, it would either break or show you one of those annoying "browser not supported" messages.

Enter jQuery, which abstracted access over all these different interfaces with a common (and very nicely designed) one. Not only did it have a fluent interface that allowed you to do multiple things with a single target (stuff like

$('#myElement').show().css({opacity:0.7}).text('My text');), but it was extensible, allowing third parties to add modules that would allow even more functionality (

$('#myElement').doSomethingCool();). Sound familiar? Extensibility seems to be an important common feature of well designed adapters.

Speaking of jQuery, one very used feature was

jQuery.browser, which told you what browser you were using. It had a very sophisticated and complex code to get around the quirks of every browser out there. Now you had the ability to do something like

if ($.browser.msie) say('OMG! You like Microsoft, you must suck!'); Guess what, the browser extension was deprecated in jQuery 1.9 and not because it was not inclusive. Well, that's the actual reason, but from a technical point of view, not political correctness. You see, now you have all this brand new interface that works great on all browsers and yet still your browser can't access a page correctly. It's either an untested version of a particular browser, or a different type of browser, or the conditions for letting the user in were too restrictive.

The solution was to rely on

feature detection, not product versions. For example you use another Javascript library called

Modernizr and write code like

if (Modernizr.localstorage) { /* supported */ } else { /* not-supported */ }. There are so many possible features to detect that Modernizr lets you pick and choose the ones you need and then constructs the library that handles each instead of bundling it all in one huge package. They are themselves extensible. You might ask what all this has to do with libraries in .NET. I am getting there.

The last example:

Entity Framework. This is a hugely popular framework for database access from Microsoft. It would abstract the type of the database behind a very nice (also fluent) interface in .NET code. But how does it do that? I mean, what if I need SQL Server? What if I want MongoDB or PostgreSQL?

The way is having different "

providers" to translate .NET code

Expressions into whatever the storage needs. The individual providers are added as dependencies to your project, without the need for Entity Framework to know about them. Then they are configured for use in code, because they implement some common interfaces, and they are ready for use.

Principles for adapters

So now we have some idea about what is good in an adapter:

- Ease of use

- Common interface

- Extensibility

- No direct dependency between the interface and what is adapted

- An interface per feature

Now that I wrote it down, it sounds kind of weird: the interface should not depend on what it adapts. It is correct, though. In the case of Entity Framework, for example, the provider for MySql is an adapter between the use interface of MySql and the .NET interfaces declared by Entity Framework; interfaces are just declarations of what something should do, not implementation.

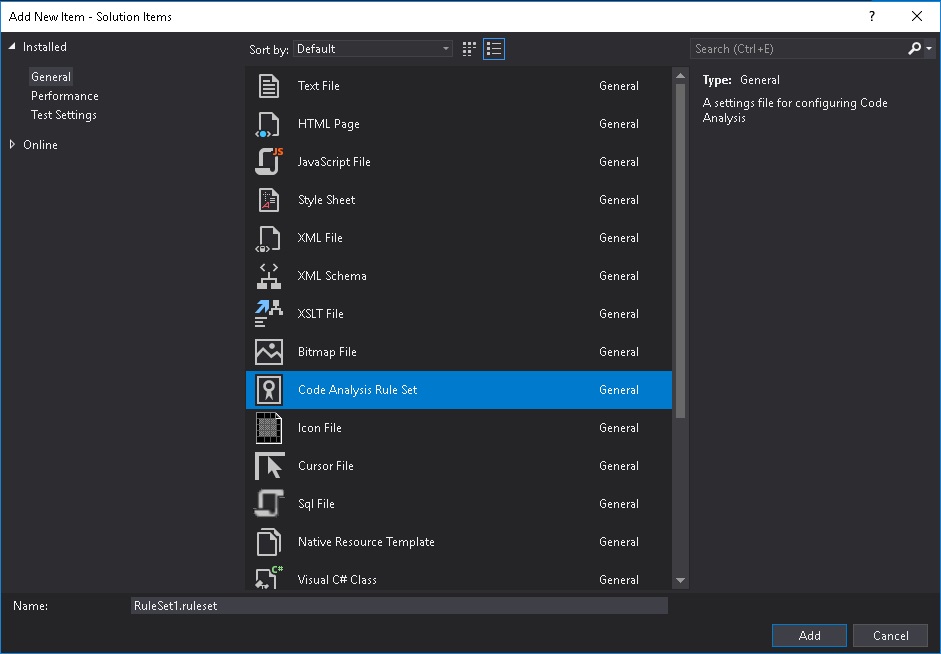

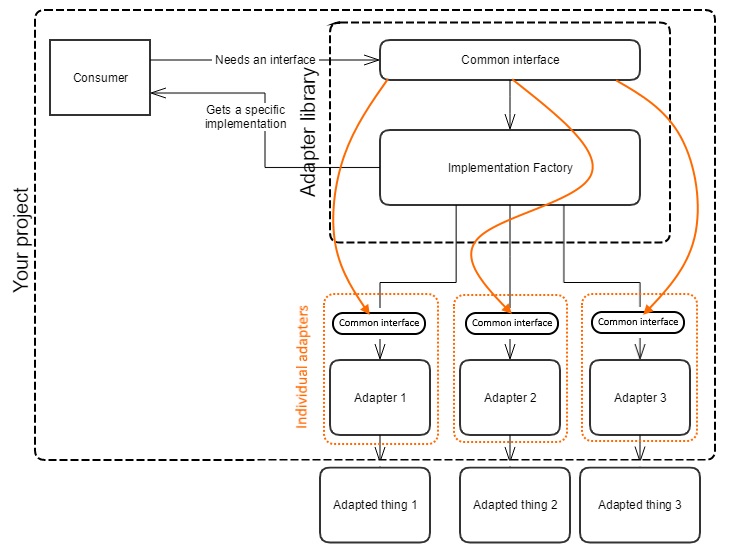

Picture time!

The factory and the common interface are one library that will use that library in your project. Each individual adapter depends on it, as well, but your project doesn't need to know about it until needed.

Now, it's your choice if you register the adapters dynamically (so, let's say you load the .dll and extract the objects that implement a specific interface and they know themselves to what they apply, like FtpWebRequest for

ftp: strings) or you add dependencies to individual adapters to your project and then manually register them yourself and strong typed. The important thing is that you don't reference the factory library and automatically be forced to get all the possible implementations added to your project.

It seems I've covered all points except the last one. That is pretty important, so read on!

Imagine that the things you want to adapt are not really that similar. You want to force them into a common shape, but there will be bits that are specific to one domain only and you might want them. Now here is

an example of how NOT to do things:

var target = new TargetFactory().Get(connectionString);

if (target is SomeSpecificTarget specificTarget) {

specificTarget.Authenticate(username, password);

}

target.DoTargetStuff();

In this case I use the adapter for Target, but then bring in the knowledge of a specific target called SomeSpecificTarget and use a method that I just know is there. This is bad for several reasons:

- For someone to understand this code they must know what SomeSpecificTarget does, invalidating the concept of an adapter

- I need to know that for that specific connection string a certain type will always be returned, which might not be the case if the factory changes

- I need to know how SomeSpecificTarget works internally, which might also change in the future

- I must add a dependency to SomeSpecificTarget to my project, which is at least inconsistent as I didn't add dependencies to all possible Target implementations

- If different types of Target will be available, I will have to write code for all possibilities

- If new types of Target become available, I will have to change the code for each new addition to what is essentially third party code

And now I will show you two different versions that I think are good. The first is simple enough:

var target = new TargetFactory().Get(connectionString);

if (target is IAuthenticationTarget authTarget) {

authTarget.Authenticate(username, password);

}

target.DoTargetStuff();

No major change other than I am checking if the target implements IAuthenticationTarget (which would best be an interface in the common interface project). Now every target that requires (or will ever require) authentication will receive the credentials without the need to change your code.

The other solution is more complex, but it allows for greater flexibility:

var serviceProvider = new TargetFactory()

.GetServiceProvider(connectionString);

var target = serviceProvider.Get<ITargetProvider>()

.Get();

serviceProvider.Get<ICredentialsManager>()

?.AddCredentials(target, new Credentials(username, password));

target.DoTargetStuff();

So here I am not getting a target, but a service provider (which is another

software pattern,

BTW), based on the same connection string. This provider will give me implementations of a target provider and a credentials manager. Now I don't even need to have a credentials manager available: if it doesn't exist, this will do nothing. If I do have one, it will decide by itself what it needs to do with the credentials with a target. Does it need to authenticate now or later? You don't care. You just add the credentials and let the provider decide what needs to be done.

This last approach is related to the concept of

inversion of control. Your code declares intent while the framework decides what to do. I don't need to know of the existence of specific implementations of Target or indeed of how credentials are being used.

Here is the final version, using extension methods in a

method chaining fashion, similar to jQuery and Entity Framework, in order to reinforce that Ease of use principle:

// your code

var target = new TargetFactory()

.Get(connectionString)

.WithCredentials(username,password);

// in a static extensions class

public static Target WithCredentials(this Target target, string username, string password)

{

target.Get<ICredentialsProvider>()

?.AddCredentials(target, new Credentials(username, password));

return target;

}

public static T Get<T>(this Target target)

{

return target.GetServiceProvider()

.Get<T>();

}

This assumes that a Target has a method called

GetServiceProvider which will return the provider for any interface required so that the whole code is centered on the Target type, not IServiceProvider, but that's just one possible solution.

Conclusion

As long as the principles above are respected, your library should be easy to use and easy to extend without the need to change existing code or consider individual implementations. The projects using it will only use the minimum amount of code required to do the job and themselves be dependent only on interface declarations. As well as those are respected, the code will work without change. It's really meta: if you respect the interface described in this blog then all interfaces will be respected in the code

all the way down! Only some developer locked in a cellar somewhere will need to know how things are actually getting done.

I didn't like Bird Box. Josh Malerman seems to be a good writer, but the way he chose a cliché as the main character just in order to skirt the explanation of what happened and avoid any actual attempts of problem solving annoyed the hell out of me.

I didn't like Bird Box. Josh Malerman seems to be a good writer, but the way he chose a cliché as the main character just in order to skirt the explanation of what happened and avoid any actual attempts of problem solving annoyed the hell out of me.