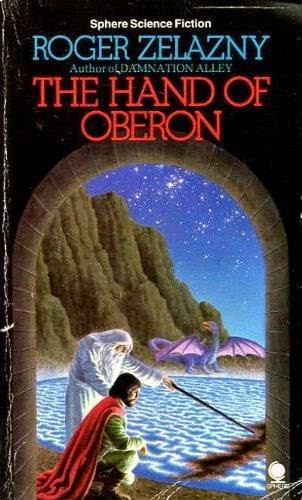

Hand of Oberon, by Roger Zelazny (Amber series book IV)

The pattern (ahem!) becomes apparent once again: same lead character doing stuff in random order just to make the story be the way it was imaged by the author, same boring exposition, same artificial drama that could have been avoided easily if Corwin would have acted like a real character and not some cardboard placeholder of the lead, same stupid and obvious twist at the end, giving the name of the book even if most of it was about something else, same lackluster secondary characters, completely oblivious and helpless if not for the main protagonist and the mighty writer god. Indeed, the mock metaphor is not so far stretched when you think that in order to do anything worthwhile, people have to step on a pattern drawn on the floor and follow the lines exactly, without stopping, or they die. Maybe so we understand the villain better, trying to spill the blood of the children of Oberon, in order to destroy the existing pattern and build one anew: a book worth reading.

The pattern (ahem!) becomes apparent once again: same lead character doing stuff in random order just to make the story be the way it was imaged by the author, same boring exposition, same artificial drama that could have been avoided easily if Corwin would have acted like a real character and not some cardboard placeholder of the lead, same stupid and obvious twist at the end, giving the name of the book even if most of it was about something else, same lackluster secondary characters, completely oblivious and helpless if not for the main protagonist and the mighty writer god. Indeed, the mock metaphor is not so far stretched when you think that in order to do anything worthwhile, people have to step on a pattern drawn on the floor and follow the lines exactly, without stopping, or they die. Maybe so we understand the villain better, trying to spill the blood of the children of Oberon, in order to destroy the existing pattern and build one anew: a book worth reading.In The Hand of Oberon, Roger Zelazny again throws his Corwin character into a series of unlikely events, wooden dialogues and implausible behaviors. All strange events, that by all established rules should not be possible, are completely ignored by the characters until they appear relevant to some great reveal. Again a villain must walk the pattern and they must stop him, by posting guards, by walking the pattern after him, yadda yadda yadda. No one even considers taking a stone off the ground and hitting him on the head with it while they are hopping around the magical Hopscotch (not to mention a rubber bullet gun which would have solved everything in most situations). No one interrogates the corroborating witnesses or the people involved in the same situations until it is too late and they themselves don't act unless confronted later on in a sort of "oh, yeah" moment that is nothing but embarrassing.

The ending is just as muddled, with a scene that sees the villain put in storage for later use and a great reveal that had been obvious for a book and a half. No one seems to really care that the shadow realms have different rates of time passage either, so instead of using some trump to go to the fastest realm to talk or plan and return with entire plans made up, they sit around in feudal palaces in Amber, looking all important. I mean, Zelazny never truly describes their attire (unless it's some girl, and then he must describe her to the size of her cups), but I think that a kevlar shirt and some blue jeans and sneakers would have done wonders to the politics of the place. Oh yeah, kevlar probably doesn't work in Amber.

One book to go until the protagonist changes. At least there is some hope there...