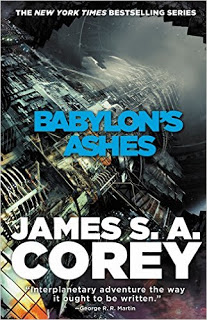

Babylon's Ashes (The Expanse #6), by James S.A. Corey

I was left a little disappointed by the books in the Expanse series. The TV show was doing great with the ideas in the books masterfully woven together, while the books were turning more and more into pulp. The greatest sin, for me, was that they took the action out of the Solar System, which was the main quality of the Expanse concept. Well, I am happy to report that, without a large increase in quality, Babylon's Ashes has returned to be a Solar System story, complete with intrigue, space war, politics and the Rocinante finding itself in the middle of everything important, again. It may be formulaic, but it's the formula that I like! Plus, it is clear that the quality of the TV show is feeding back into the books, which is great.

I was left a little disappointed by the books in the Expanse series. The TV show was doing great with the ideas in the books masterfully woven together, while the books were turning more and more into pulp. The greatest sin, for me, was that they took the action out of the Solar System, which was the main quality of the Expanse concept. Well, I am happy to report that, without a large increase in quality, Babylon's Ashes has returned to be a Solar System story, complete with intrigue, space war, politics and the Rocinante finding itself in the middle of everything important, again. It may be formulaic, but it's the formula that I like! Plus, it is clear that the quality of the TV show is feeding back into the books, which is great.So Holden and Naomi need to deal with the fact that her psychotic ex-boyfriend and father of her child is a mass murderer who is leading the whole Solar System to war, chaos and finally starvation. Some characters die, which put Holden even more in the spotlight. Quite pointless characters are preserved, like Prax, which I personally despise, and others are added, like the pirate captain Michio Pa. In this book, the authors are tying up the loose ends: the state of the Solar System, the war, the situation at Medina station. The path toward the future is still in the balance at the end of the book. It's almost like asking "so, do we do cool Belter culture Solar System stories or do we pulp it out in the alien worlds?". Well, I will read Persepolis Rising next.

Conclusion: I liked the book enough to read it in a day or two and it made me want to read the series again.