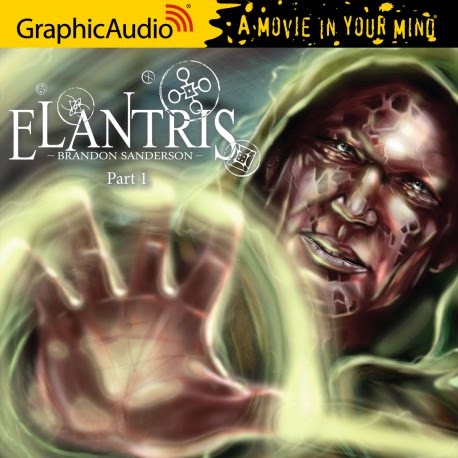

Elantris, by Brandon Sanderson

In a world dominated by trilogies and quadrilogies and sagas, it is refreshing to see that some people are writing stand-alone fantasy books. I've first heard of Brandon Sanderson when he ended up writing the last books in the Wheel of Time series, after its initial author died; those books were the best in the series, even if he had to work with Jordan's notes. Recently, I've stumbled upon this audio adaptation of Sanderson's book Elantris, produced by Graphic Audio, a company that doesn't just created narrations of books, but full audio plays - while changing nothing of the initial text.

In a world dominated by trilogies and quadrilogies and sagas, it is refreshing to see that some people are writing stand-alone fantasy books. I've first heard of Brandon Sanderson when he ended up writing the last books in the Wheel of Time series, after its initial author died; those books were the best in the series, even if he had to work with Jordan's notes. Recently, I've stumbled upon this audio adaptation of Sanderson's book Elantris, produced by Graphic Audio, a company that doesn't just created narrations of books, but full audio plays - while changing nothing of the initial text.Despite some parts being a bit too optimistic, some too slow and some really obvious - waiting for a character to catch up with you is not fun - the book was really entertaining and original. It also was Sanderson's first widely released book, so I can forgive his lack of perfection :). I really liked the story and the characters in the book. In truth, the book's message is one of hope, one of encouragement toward the human spirit becoming the best it can be. I couldn't help thinking that Sanderson probably portrayed himself in Raoden, and that guy is great.

Anyway, the plot revolves around the magical city of Elantris, populated by God like creatures that shine with the light of magic and are almost omnipotent. However, the story starts ten years after a horrible collapse of said city, which transformed every Elantrian into an immortal husk, heart not beating, hair falling, skin blotched by dark spots, incapable of healing the smallest cut or bruise, but fully capable of pain, unneeding of food, but fully able to feel ravenous hunger at all times. The process, called Shaod, has not ended, it still occasionally picks people at random and turns them into these creatures of eternal pain. The human inhabitants of nearby towns have quarantined Elantris and anyone affected by the Shaod is thrown inside the rotting city.

There are two main characters: prince Raoden and his bride to be, princess of a nearby kingdom, called Sarene. Not only them, but almost every actor is full of spirit (pun intended) and really likable, even the antagonists can be understood and sympathized with. The story is full of events that lead to character development, politics, smart plotting, drama and comedy.

Well, in the end, with all my talk of stand alone books, I was a bit sad to see the story end. I wanted more, and that's a good sign, right? Sanderson is supposedly considering writing a sequel, but it's not something that will happen soon and it will involve different characters. I liked Elantris and I recommend it to all fantasy fans.