Fighting the Cunningham defense (King's Gambit accepted)

Whenever I want to share the analysis of a particular opening I have difficulties. First of all, I am not that good at chess, so I have to depend on databases and computer engines. People from databases either play randomly or don't play the things that I would like to see played - because they are... uncommon. Computer engines, on the other hand, show the less risky path to everything, which is as boring as accountants deciding how a movie should get made.

Whenever I want to share the analysis of a particular opening I have difficulties. First of all, I am not that good at chess, so I have to depend on databases and computer engines. People from databases either play randomly or don't play the things that I would like to see played - because they are... uncommon. Computer engines, on the other hand, show the less risky path to everything, which is as boring as accountants deciding how a movie should get made.

My system so far has been to follow the main lines from databases, analyze what the computer says, show some lines that I liked and, in the end, get a big mess of possible lines, which is not particularly easy to follow. Not to mention that most computer lines, while beautiful in an abstract kind of way, would never be played by human beings. Therefore, I want to try something else for this one. I will present the main lines, I will present how I recommend you play against what people have played, but then I will try to condense the various lines into some basic concepts that can be applied at specific times. Stuff like thematic moves and general plans. It's not easy and I may not be able to pull it off, but be gentle with me.

Today's analysis is about a line coming from the Cunningham Defense played against the King's Gambit, but it's not the main line. It's not better, but not really worse either. I think it will be surprising to opponents.

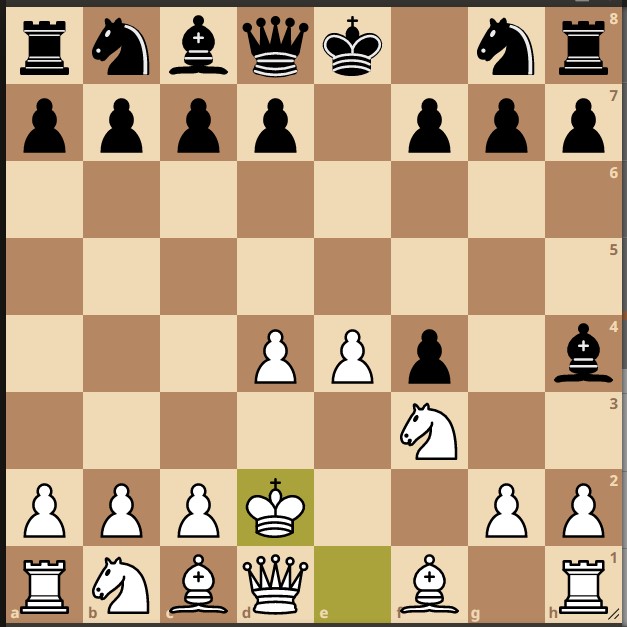

We start with King's Gambit accepted: e4 e5 f4 exf4 Nf3, which is the best way to play against the gambit, according to machines and most professional players. Now, Black plays Be7 - the Cunningham defense, with the sneaky plan of Bh4+, Nxf4, Qh4+, forcing the king to move or try to futilely block with g3 and lose badly (or enter the crazy Bertin Gambit, which is very cool, too). Amazingly, there is little White can do to prevent this plan! White entered the King's Gambit with the idea to get rid of the pawn on e5 and play d4, controlling the center. The main line says that, after Be7 by Black, White's light square bishop has to move, Bc4 for example, making way for the king to move to f1.

What I want to do, though, is not to move the bishop, but instead continue with the d4 plan. I am going to show you that moving the king is not that bad and that, succeeding in their plan, Black may overextend and make mistakes. There are some traps, as well. The play, though, has to be precise.

And I dare you to find anybody talking about this particular variation! They all assume Bc4, h4, Nc3 or Be2 are the only options.

Let's start with the main lines, in other words, what people play on LiChess from that position:

As you can see, most played moves are bad, starting with the very first one: Ke2. Instead, what I propose is Kd2, with the idea c3, followed by Kc2. The king is relatively safe and there are some naturally looking moves that Black can end up regretting. Next stop, playing correct moves vs the most commonly played moves on LiChess:

While it doesn't give an obvious advantage - what I propose is not a gambit, just a rare sideline with equal chances, it gives Black plenty of opportunity to make a mistake. Let's see where Black's play on LiChess agrees with Stockfish strategy and note that Black never gets a significant advantage, at the human level closest to perfect play:

Finally, before getting to the condensed part, let's see how Black can mess things up:

Note that there are not a lot of games in this variation, so the ideas you have seen above go just as far as anyone has played in that direction. Computer moves are wildly different from what most people play, that is why machines can be good to determine the best move, but they can hardly predict what humans would do.

In conclusion, without blundering, Black keeps an extra pawn but less than 1 pawn evaluation advantage, meaning White always keeps the initiative, despite having the king in the open.

White's plan is to keep control of the center with e4, d4, followed by c3 and Kc2, Bd3 or Bb5+, Bxf4, Nd2, etc. White's greatest problem are the rooks which need a lot of time to develop. The attack can proceed on the queen's side with Qb5 or on the king's side with pushing the pawns, opening a file for the rook on h1. It's common to keep the dark square bishop under tension on h4, blocking Black's development, but then take it and attack on the weakened dark squares or on the queen's side, once Black's queen in on the other side of the board.

I would expect players that are confident in their endgames to do well playing this system, as most pieces are getting exchanged and opponents would not expect any of these moves.

Here are some of the thematic principles of this way of playing:

- After the initial Bh4+, move the king to d2, not e2, preparing c3 and Kc2

- while blocking the dark squares bishop, it uses the overextended Black dark square bishop and the pawn on f4 as a shield for the king

- if d5, take with exd5 and do not push e6

- opens the e-file for the queen, forcing either a queen exchange or a piece blocking the protection of the h4 bishop from the queen

- a sneaky intermediate Qa4+ move can break the pin on the queen and win the bishop on h4

- if d6, move the light square bishop

- Bd3 if the knight on b8 has not moved

- allows the rook to come into the game and protects e4 from a knight attack (note that Nf6 breaks the queen defense of h4, but Nxe4 comes with check, regaining the piece and winning a pawn)

- Bb5+ if the knight has moved

- forces the Black king to move. If Bd7, then Bxd7 Kxd7 (the queen is pinned to the bishop on h4)

- note that if Nc6 now, d5 is not a good move, as it permits Ne4 from Black

- Qb5+ can win unprotected pieces on g5 or h5

- Bd3 if the knight on b8 has not moved

- once both Black bishops are active on the king's side, c3, preparing Kc2 and opening the dark square bishop to take the pawn on f4

- play c3 on d6 followed by Nc6 as well

- Nc6 is a mistake if there is no pawn at d6. Harass the knight immediately with d5:

- Na5 is a blunder, b5 traps the knight

- Nb5 gives White c3 with a tempo, preparing Kc2

- Nb1 is actually best, but it gives White precious tempi (to play c3)

- White's c4 instead of c3 is an option, to use only after Bg5, preparing Nc3

- c4 might seem more aggressive, but it blocks the diagonal for the light square bishop

- c4 may be used to protect d5 after a previous exd5

- c4 may be used after a bishop retreat Be7 followed by Nf6 to prevent d5

- White's Kc2 prepares Bxf4, which equalizes in most cases by regaining the gambit pawn

- Black's Nf6 blocks the queen from defending the bishop on h4, but only temporarily. Careful with what the knight can do with a discovered attack if the bishop is taken.

- usually a move like Bd3 protects e4. After Nxh4 Nxe4 Bxe4 Qxh4 material is equal, but Black has only the queen developed and White can take advantage of the open e-file

- Kc2 also moves the king from d2, where the knight might check it

- Keeping the king in the center is not problematic after a queen exchange, so welcome one

- Qe1 (with or without check) after Nxh4, Qxh4 is a thematic move for achieving this

- One of Black's best options is moving the bishop back Be7, followed by Nf6. However, regrouping is psychologically difficult

- in this situation c4 is often better than c3

- After Bg4, Qb5+ (or Qa4+ followed by Qb5) unpins the queen with tempo, also attacking b7 and g5/h5

I hope this will come in handy, as a dubious theoretical line :) Let me know if you tried it.

Update:

After analyzing with a bunch of engines, I got some extra ideas.

For the d5 line, pay some attention to the idea of taking the bishop with the knight before taking on d4. So Kd2 d5 Nxh4 Qxh4 exd5. I am sure engines find an edge doing it like that, but I feel that at the level of my play and that of people reading this blog (no offence! :) ) it's better to keep the tension and leave opportunities for Black to mess up.

Another interesting idea, coming from the above one, is that the Black queen needn't take the knight! Taking the pawn (dxe4) and developing the knight (Nf6) are evaluated almost the same as Qxh4! This is an idea for Black, I won't explore it, but damn, it seems like no one loves that horsey on h4!

Then there are the ways to protect the doubled pawn on d5, either with c4 or Nc3. Nc3 is not blocking the light square bishop and allows for some possible traps with Bb5+, yet it blocks the c-pawn, disallowing Kc2. c4 feels aggressive, it allows both a later Nc3 and Kc2, but leaves d4 weak. Deeper analysis suggests c4 is superior, but probably only in the d5 lines.

When Black's queen is on h4, White needs to get rid of it. Since the king has moved, an exchange is favorable, but it also removes the defender of the pawn on f4.

Some rare lines, Black plays Nh5 to protect f4. The strange, but perfectly valid reply, is to move the knight back, allowing the queen to see the Black knight: Ne1 or even Ng1.

In positions where the king has reached c2 and there is a Black knight on c6, prevent Nb4 with an early a3.

In the d6 line, Black has the option to play c5, attacking the pawn on d4. Analysis shows that dxc5 is preferred, even when the semifile towards lined up king and queen opens and the pawn takes towards the edge. Honestly, it's hard to explain. Is the c-pawn so essential?

If you've read so far, I think that the best way for Black to play this, the refutation of this system so to speak, is bishop back Bg7 followed by Nf6. And the interesting thing is that the reply I recommended, c4 preventing d5, may not be superior to Nb3 followed by exd5.

Comments

Be the first to post a comment